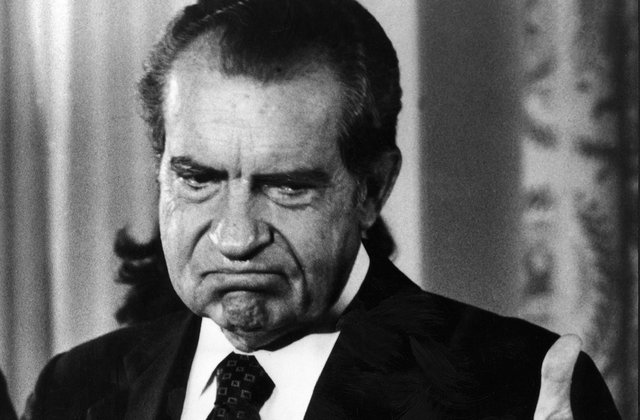

It would appear that the alienation of white people from Civil Rights was a key product of Black Power. An indication that this was occurring was the election of Richard Nixon in 1968 and his re-election in 1972 on a ‘law and order’ ticket. But, this perspective is short-sighted.

In some ways, the most obvious result of Black Power was to drive away white support. This was true in at least two respects – Stokely Carmichael’s decision to turn SNCC into a black-only organisation and his decision to turn away from the Civil Rights Movement’s goal of integration. Unfortunately, the timing of his proclamation of black power coincided with a period of rioting throughout America, beginning in the Watts district of Los Angeles in 1965, between 11th and 17th August, resulting in 34 deaths, 1000 injuries and nearly 4000 arrests as well as the destruction of hundreds of shops, businesses and homes. Similar riots went on in other cities and particularly in 1968, following the assassination of Martin Luther King, another 110 cities fell into violence resulting in 200 deaths. Whilst none of these events were organised by SNCC, the Black Panthers or any other black organisation, it was easy for city authorities to blame the influence of Black Power, even though the Government’s Kerner Report showed that rioting was in fact a direct consequence of inequality and poverty, not black ideology. In the context of these developments, the actions of Tommie Smith and John Carlos in October at the 1968 Mexico Olympics may have contributed to a sense of alienation among some sections of the white community. While their actions have been celebrated since, neither were able to compete for their country again – despite Tommy Smith’s world record breaking performance in the 200 meters (he remained the only human being to run 200 meters in less than 20 seconds until Carl Lewis broke his record in 1984).

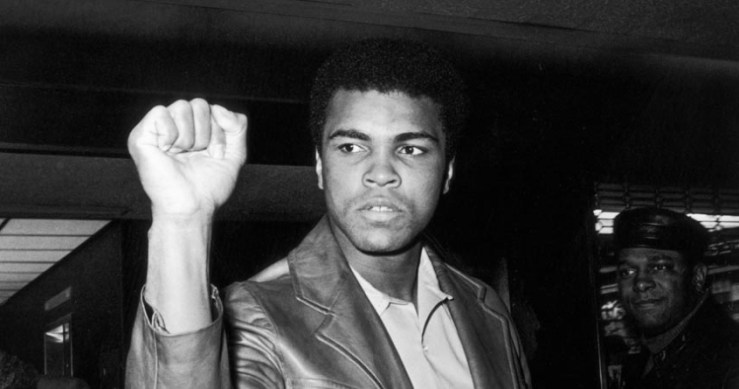

Lest we forget, the greatest heavyweight boxer of all time, Muhammad Ali, was a supporter of black power as well as a member of the Nation of Islam. The white press did not celebrate him then as it does today. Instead it saw him as ‘arrogant’ and it was keen to see him fall. The conservatives got thier way, of course, cruelly stripping Ali of his world title and then his boxing licence in 1967, for refusing the draft. Ludicrously, Ali was convicted of draft-dodging on the grounds that his Islamic beliefs were not sincerely held. Over the next three years, he toured American universities and college campuses giving speeches in which he emphasised the pacificism inherent in Islam – not something regularly associated with Black Power at the time or since, and revealing of its complexity. Ali called the Vietnam War a “war of domination of slave masters over the darker people of the earth”. Ali’s real crime, in the eyes of conservatives, was his refusal to play an ‘acceptable’ role in society, which meant ‘knowing his place’. The day after he first defeated heavyweight champion Sonny Liston in 1964, to claim the world heavyweight title for the first time, Ali was asked by a reporter if he was a card-carrying member of the Nation of Islam. To this, Ali replied, ‘Card-carrying? What does that mean? I know where I’m going, and I know the truth, and I don’t have to be what you want me to be. I’m free to be what I want to be.”

The alienation of white people was probably a more important effect of Black Power than its limited practical impact on the ghettos. The key organisation that went to work on such issues, the Black Panther Movement, was operational across 25 cities, and focussed on improving the lives of black people by undertaking charity work, educational drives, breakfast clubs for children, and acting as a kind of ‘black police force’. However, the Black Panthers were never more than 2000 members strong, meaning that their direct impact was always going to be limited. Moreover, their aggressive behaviour towards the police, their paramilitary dress code, their carrying of weapons, and frequent shoot-outs, meant that any good they did for their own communities may have been outweighed by the damage they did to the image of those communities among white people, by helping to justify the view that the rioting in American cities was a direct result of Black Power. Such attitudes not only helped bring Richard Nixon to power in 1969 but meant that once in power he could ignore the findings of the Kerner report and its demands for investment in the inner cities. At the very least, it meant that he could direct investment towards law enforcement agencies rather to the communities that needed it most. His ‘law and order’ ticket dealt with the consequences of social problems, not their cause.

Yet Black Power had other important effects. In particular, although Black Power was not focussed on achieving the same goals as the Civil Rights Movement, it is perhaps the case that organisations like the Nation of Islam, and critics like Malcolm X, encouraged authorities to believe that it was better to yield to the peaceful protesters rather than risk those who demanded change ‘by any means necessary’. To that extent, Black Power may have played an indirect role in promoting Civil Rights. But this is not the only reason Black Power was significant. To understand why we need look no further than the career of Martin Luther King – the target of Malcolm X’s jibes in the early 1960s. After 1965, King focussed more on social and economic issues than he had before 1964, an indication that he too had been influenced by the message of Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael following the March Against Fear. In 1967, King told his audience at the annual convention of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) on August 16, “No Lincolnian Emancipation Proclamation, no Johnsonian civil rights bill” could bring about complete “psychological freedom.” The Negro must “say to himself and to the world . . . ‘I’m black, but I’m black and beautiful.’” In the book he published in the same year, entitled Where do we go from here?, King wrote ‘Power is not the white man’s birthright; it will not be legislated for us and delivered in neat government packages’. In his opposition to the war in Vietnam which he proclaimed in April 1967, King finally broke with the Lyndon Johnston administration that had achieved landmark civil rights legislation in 1964 and 1965: an indication that in his last years he had become more radical than he had ever been during the days of Montgomery and ‘I have a dream’. A year to the day after his Vietnam speech, he was assassinated by a white supremacist. Although non-violent strategies and the focus on integration and equality had helped to achieve the greatest advances in Black emancipation since the Emancipation Proclamation itself, Martin Luther King recognised that its achievements were still not enough. Black Power spoke to the anxieties of people in the north in way that the southern Civil Rights’ Movement never could. Their experience of discrimination came not in the form of a segregation demanded by law but in the lack of opportunities for education, employment, and housing. That was discrimination not at the hands of Jim Crow or the KKK, but at the hands of everyday government officials, the police, employers and fellow citizens.

Although non-violent strategies and the focus on integration and equality had helped to achieve the greatest advances in Black emancipation since the Emancipation Proclamation itself, Martin Luther King recognised that its achievements were still not enough. Black Power spoke to the anxieties of people in the north in way that the southern Civil Rights’ Movement never could. Their experience of discrimination came not in the form of a segregation demanded by law but in the lack of opportunities for education, employment, and housing. That was discrimination not at the hands of Jim Crow or the KKK, but at the hands of everyday government officials, the police, employers and fellow citizens.

The failure of the Civil Rights Movement to achieve the goals of King’s Lincoln memorial speech almost 60 years’ later means that ‘Black Power’ is more relevant to black people today than it even was in 1968. To blame Black Power for the failure of the progress of Civil Rights after 1968 is to create a narrative that blames the oppressed for their problems. The progress of Civil Rights ground to a halt in the late 1960s not because of Black Power but because war in Vietnam had distracted America, and because the hostility of southern Democratic voters to Civil Rights finally turned them against the party they had voted for since before the Civil War. They turned first to the openly racist agenda of George Wallace in the 1968 election, thereby enabling Nixon to take the presidency by dividing the Democratic vote, and eventually to Richard Nixon himself, after he had promised ‘law and order’ in his ‘southern strategy’ election campaign of 1972. This is why the solid Democratic South became, and remains, the Solid Republican South. Those voters were not alienated from Civil Rights by Black Power because they were never supporters of Civil Rights in the first place. Finally, and most shamefully, if erstwhile supporters of Civil Rights were indeed alienated from the movement by Black Power, it was because they believed that with the legislative changes of the mid-1960s the Civil Rights question had finally been resolved. They either didn’t hear or didn’t want to hear about the problems that would take a lot longer and a lot more investment to fix. For such people, Black Power became an excuse to look the other way.

The Australian athlete, Peter Norman, who participated in the Black Power protest at the 1968 Olympics, suffered the same fate in Australia as Smith and Carlos in America: it cost him his athletic career. When he died, Smith and Carlos helped to carry his coffin. But Peter Norman’s support for Smith and Carlos is an indication that not all white people were alienated by Black Power* nor naive enough to believe that black problems had been magically resolved. Muhammad Ali’s conviction for draft dodging was eventually overturned by the Supreme Court on a technicality and he narrowly avoided going to jail. Against all the odds, he won the heavyweight title again in 1974, 10 years he first won the title, defeating the much younger George Foreman in the ‘rumble in the jungle’ held in Zaire, a post-colonial state led by a black leader. The boxers were flown to Zaire by black pilots and the fighting was accompanied by a major concert featuring top US and African black musicians. Whatever Black Power may have meant for conservative whites, it had a unifying effect on black populations across the globe. While some sections of the white community may have been alienated by black riots and fallaciously connected them to Black Power in the late 1960s, Black Power was a response to – and not the cause of – the problems that divided American society in 1968 and which still divide it today. Whatever the most important impact of Black Power, it ought to be a deeper awareness and understanding of the problems it sought to draw attention to.

*Thank you to Nicholas Johnston a pupil who pointed this out to me in a year 10 essay on this topic.