That morning, at Troy, it was tempting to believe that if the gods were once ever present, they left the place to itself a long time ago. Yet once, in Homer’s world, each turn, each twist of the ten years of the Trojan War saw the Gods intervene to save, to maim, to kill.

We don’t really have gods anymore. The vast majority of the men who fought on the Gallipoli peninsula beloved in God: one God. They were men of the great religions of the book. Many sought the solace of God in the face of what was one of the most brutal and hard fought campaigns of a war hardly short on either. Some prayed for God to save them. It is perhaps at times like that that the divine will is hardest to fathom of all. For some, of course, it was hardly God’s will at all, if at all: who got hit, who survived, was pure luck, simple fate. The gods, even God, or fate killed many men at Gallipoli. Among the many more spared were two men, one on each side, who changed the history of both our countries.

Mustafa Kemal was a professional soldier. By the time of Gallipoli, he was famously a leader of men, pulling all together, famous for his almost reckless heroism under fire and his ability to lead men to fight and die willingly for their motherland: ‘I do not order you to fight, I order you to die.

. Clement Attlee was cut from a very different cloth. Coming from a comfortably off middle class family, the son of and Anglican churchman, Attlee was a public schoolboy and, like so many of his class, joined up after the declaration of war in 1914. He was made an officer, something his schooling had well prepared him for and, as such, he found himself on the other side of the Gallipoli landings.

Clement Attlee was cut from a very different cloth. Coming from a comfortably off middle class family, the son of and Anglican churchman, Attlee was a public schoolboy and, like so many of his class, joined up after the declaration of war in 1914. He was made an officer, something his schooling had well prepared him for and, as such, he found himself on the other side of the Gallipoli landings.

On the Turkish side, Gallipoli was might be claimed a victory, even if one at a terrible price: best estimates of their dead are of around 80,000. German gunnery, training and resources certainly helped, though even the Germans felt that it was the psychological strength of the defenders that proved decisive: the Turks here (unlike in the rest of their empire) were fighting for their homeland. And the unforgiving nature of the terrain hardly helped the Allies; nor did sometimes amateurish preparation, and command, or over-optimistic political leadership help.

In the Ottoman Empire before the First World War, a generation of younger army officers were highly politicised, partly due to a frustration at the antiquated structures of the Ottoman state, borne in part of a westernising and modernising outlook, and in part thanks to the decline of the Ottoman Empire in the context of the rising power of Europe since the 17th century. The Young Turks, as they were known, wanted constitutional politics but, increasingly, looked to Turkish nationalism as the answer.

Attlee’s Haileybury was a school noted for its high moral tone and Christian evangelicalism. At school, he lost his faith, and after university and his qualification as a lawyer, he started to do charitable work in the East End of London, through an organisation known as Toynbee Hall. That experience changed him, and led him from his native Conservatism to socialism. While Attlee may have lost his faith, like many of the second generation of middle class socialists, Attlee’s politics inherited that high moral tone and perhaps even something of the paternalism of his conventional Anglican upbringing.

The war changed Kemal, and changed Turkey. If Turkish nationalism had become predominant among the younger officers of Kemal’s ilk before the war, it became wholly dominant during and after. Having been shunted off to fight in the Middle East after Gallipoli, as the old empire tottered to inevitable defeat in 1918 Kemal found himself organising the last ditch defence of Anatolia. Though, with a characteristic realism, he was to recommend surrender then, Kemal found the Allied occupation of Istanbul hateful. He found the terms of the post-war Treaty of Sevres intolerable: it granted substantial lands to Greece, including in Asia Minor, independence to Armenia and autonomy to the Kurds. The result was the decision to gather the Anatolian forces together and overturn the sultan, the treaty and to create a new Turkey. Had Kemal been killed at Gallipoli, one can only wonder what might have happened.

In Britain, the Liberal Party that had lead Britain to war in 1914 and subsequently torn itself apart, primarily over the premiership of David Lloyd George. By 1922, he was the Liberal prime minister of a government dominated by Tories, many of whom wanted rid of him. By 1922, Kemal had ousted the sultan and British forces withdrew from Istanbul; the last British forces left were a token force of around 300 policing the straits of the Dardenelles the British and Turks had fought over so bitterly in 1915. When Turkish forces were turned on them, at Cannakkale, Lloyd George gave the local commander, Harrington, the order to stand firm and await relief from the navy. War, it seemed, was possible. In the end, Harrington disobeyed orders, claiming that his decoding machine had broken down. Soon after, the British withdrew.

The Chanak Crisis served to crystallise Tory fears about Lloyd George. Within a few weeks, he was ousted from office; there hasn’t been a Liberal prime minister since.

Kemal went on to create the secular Turkish Republic: the last Sultan was deposed in 1922, he fled into exile the following year. Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, as he now became, set about reforming his nation, seeking to turn the ramshackle old empire into a modern European state. He introduced the Roman alphabet and began to create an education system (95% of Turks were illiterate); he adopted a new western legal code, introduced the western Gregorian calendar, replaced Friday as the day of rest with Sunday and had all Turks take on surnames. He also outlawed many long established customs, including the fez, traditional dress and polygamy.

It is fair to say that Kemal’s revolution was less than democratic, in an age where democracy was not the European norm; Kemal’s own dictatorial nature hardly helped. The priority, above all else, was the assertion of national independence. In the face of that and the parlous state of government finances, other priorities (such as the weakness of the Turkish economy, the dire poverty of most of the overwhelmingly rural population and the lack of modern infrastructure) were largely ignored. Kurds, Armenians and other minorities fare even worse. Turkey had achieved nationhood, but at this expense of its own people.

In retrospect, the fall of Lloyd George was both important in itself, but was also powerfully symbolic. In the election that followed, the Labour Party polled 30% of the popular vote, won 141 seats and became established as the second party in British politics, usurping the place on the centre-left the Liberals had previously dominated it. By 1924, they had formed a minority government, as they would again in 1929. The Liberals were a spent force.

Had Lloyd George not fallen, then Churchill may never have crossed the floor at all; had the Liberals not allowed Labour to govern in 1924, the rabidly anti-socialist Churchill may well have stayed Liberal. It was a well timed defection: in the 1924, election the Liberals were all but destroyed (reduced to a mere 40 seats), and Churchill returned to high office as Chancellor of the Exchequer in a Conservative government.

If Kemal’s Turkey was never a real democracy; after 1928, Britain very much was. In 1931 the electorate delivered a devastating verdict on the Labour Party: it still won 30% of the vote, but was reduced to 52 seats as its former leader, Ramsay MacDonald, as prime minister of a Conservative dominated National Government, won one of the biggest landslides in British political history. Ironically, that defeat was probably one of the best things to happen to Labour, and to Clement Attlee. The 1931 annihilation stripped Labour of most of its MPs, and with that most of its established leadership. The parliamentary party was initially led (ineffectually) by the veteran left-winger George Lansbury. In reality, the Labour Movement was led by the trade unions. When Lansbury Was forced out by Ernest Bevin and the unions, the parliamentary leadership fell to one of the few ministers from the last government to survive: Clement Attlee’s hour had come.

Famously, the ‘thirties were Churchill’s wilderness years, out of office and often in opposition to his own government. He railed against Indian independence, in favour of Edward VIII and in opposition to appeasement. It was only war that brought Churchill back into office and, the following year, to create a true National Government.

Thus it was, by one of those ironies that history abounds in, the former Major Attlee ended up being, in effect, number two to the former First Lord of the Admiralty who had, 25 years before, been a key figure in the Gallipoli campaign’s conception. If Labour’s patriotism and ever been in doubt, it couldn’t be now; in truth, the likes of Attlee and Bevin were pretty conventional patriots. In short, Labour had a good war.

Britain’s Hungry ‘Thirties are, we now know, something of a myth. Indeed, compared to the endemic and crushing poverty of Turkey, Britain had a very comfortable time of it in the Great Depression. Nonetheless, the hardships were real and people remembered them, and the Conservatives’ inability to tackle them. In 1945, Attlee’s Labour won an unexpected (though, in hindsight, very explicable) victory.

As leader of the opposition, Attlee had overseen Labour’s adoption of a genuinely socialist platform, in contrast to MacDonald’s cautious reformism. The experience of war shifted the middle of British politics to to the left and Labour went with it. The result was one of the great British governments, transforming British society and politics, and ‘little Clem’ proved to be an astute and effective leader of it.

Kemal created a nation, but he could not clear bones. The battlefields of Gallipoli were commemorated, but only by the British and the French who, in the ‘twenties, built cemeteries and memorials. This was different to the war of a hundred years before, when in the aftermath of the battle of Waterloo bodies were left where they lay of battlefield or with graves behind the lines marked with rudimentary stones. In the new Turkey, the bones of the fallen were left where they lay, and no great memorials were built until the 1950s.

When Achilles killed Hector, he dragged Hector’s body across the very ground, dishonouring the body of his fallen enemy as soldiers have done through the ages; just as one Aussie soldier took a severed a Turkish head and took it home as a trophy of war. At Troy, the gods intervened, and Priam moved Achilles heart. Hector’s body was duly honoured.

To the modern eye it seems only fit that a great nation cherishes its own children and, when they have fallen in its cause, commemorates them fittingly? Attlee’s Haileybury like so many schools of its ilk commissioned its own war memorial. By the time Attlee was making his way into politics, the headmaster of Haileybury was the former head of the RGS in the Great War, John Talbot.

Perhaps that commemoration goes beyond cemeteries and monuments. This morning, I was chatting to a battlefield guide who was taking two serving British army officers round the Gallipoli battlefields. One remark he made jumped out at me: we underestimate the positive things Britain got from the Great War and, even, Gallipoli.

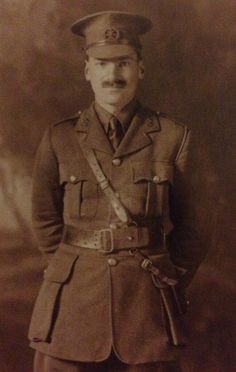

It is axiomatic now, in writing on the British Army in the Great War, to emphasise the bond that was forged between the junior officers and the men they commanded. The junior officers, at first, had almost all been public schoolboys. As such, they were trained to lead, for sure. The Christian ethos of most of those schools inculcated another element to that leadership: duty of care. That care could easily become, in the true sense of the word, love. Siegfried Sassoon, for all his profound unease about the war itself, opted to return to the front for the sake of his men. Officers, like Attlee, or Capt. Leslie Moorhead shown here surveying British and Turkish dead, mattered.

There are historians who argue that the new gods of the modern secular age were nations. In that sense Kemal was very much of a piece with that new faith. One might wonder whether that faith alone was enough. Like most men of his time and his class, in his youth Attlee imbibed a simple patriotism and a moral surety he never lost. He may have lost his Christian faith at school, and in one sense replaced it with a new one, socialism, but that had undoubted roots in his lost faith, in what we sometimes hear called Christian socialism. Attlee’s socialism was rooted in an underlying morality and even beneath that, a deep faith in the ability of humanity to work together, to aspire to make the lives of ordinary people materially and spiritually better. I grew up in a post-war council house in Essex; from my window I could see Haileybury.

When one looks at the subsequent careers of men who fought in the war they are, naturally enough, kaleidoscopic. Many went on to live the same relatively humdrum, decent and valuable lives that most of us live. Some of those whom fate spared, achieved greatness, like Kemal (Churchill served in his old regiment too). Some would be spared to do evil: among those who survived Gallipoli were Sir Oswald Mosley. Four British prime ministers served in the war (Macmillan and Eden did too). Of those, two could rightly be called great.

Perhaps, just as if we burn books we burn people after, the nation that cares for its bones will care for its people too. Of course, Churchill was great, but so too was Attlee. His socialism cared for the same sorts of people whose bones were by then buried in the cemeteries we will find around the world. Had the gods, God, or simple fate not spared him, what might have been different? Is it too much to say that the Britain his government left us with has at least one of its roots firmly set in the sandy soils of Gallipoli, looking down upon the Suvla Bay he evacuated?

Reblogged this on RGS History and commented:

To celebrate 70 years, and 100 since Gallipoli

LikeLike