Sir Herbert Samuel

Sir Herbert Samuel

1916 (under Asquith, in the wartime coalition), 1931-32 (as part of the National Government under MacDonald)

Despite having held the Home Office twice, most of the achievements of Samuel’s long life were not those in high office.

Samuel came from a wealthy Jewish background. His Jewishness would both inform his politics, and be used against him by his enemies, though many at the time felt the anti-Semitism he faced owed something to a somewhat unappealing personality. Having been educated at University College School, he won a first in History at Balliol College, Oxford. After getting to know London’s East End, and its large Jewish community, he became involved in politics, very much on the New Liberal wing of the Liberal Party. As such, and as a member of the so-called Rainbow Circle, he had close relations with many of the leading figures in Labour politics, such as the Webbs and Ramsay MacDonald. His Liberalism: its Principles and Proposals (1902) was perhaps the most important statement of the New Liberal position.

Having entered parliament in 1902, Campbell-Bannerman gave him office as under-secretary of state in the Home Office when the Liberals returned to power in 1905. Under Herbert Gladstone, he played the leading role in introducing a raft of New Liberal legislation, including the Children’s Charter and the creation of the probation system (see the article on Herbert Gladstone, here). The years that followed saw Samuel serve as postmaster general (he nationalised the telephone system) and president of the local government board. Samuel even devised the formula justifying Britain’s declaration of war in 1914 (over the issue of Germany’s violation of Belgian neutrality) that managed to hold most of government and Liberal Party together.

He was out of the cabinet when Asquith formed his wartime coalition in May 1915, but he returned when Churchill resigned as chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster in November. When Sir John Simon resigned over the issue of conscription in January 1916, Asquith gave Samuel the Home Office (Samuel was succeeded as chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster by his cousin, Edwin Montagu).

It was a brief and unhappy tenure. It was under Samuel’s watch that martial law was introduced into Ireland after the Easter Rising and that its leaders were executed. Samuel also sanctioned the hanging of Sir Roger Casement, who had been seeking German support for the Rising. His decision seems to have been coloured by Casement’s homosexuality, a subject about which Samuel had very strong views that do not sit well with the modern mind. Furthermore, he had once worked closely with Casement in opposition to the Belgian governance of the Congo. Conscientious objectors were treated harshly, and Bertrand Russell was imprisoned for his anti-war propaganda. The left-wing Liberal stood accused of betraying his liberal principles.

He was hardly alone in that. Nor was he alone in refusing to serve under Lloyd George (with whom he had a very uneasy relationship, of which more anon). However, like his predecessor in the Home Office Sir John Simon, that meant he would not be in government again until 1931. Like Simon, Samuel lost his seat in the Coupon Election of 1918.

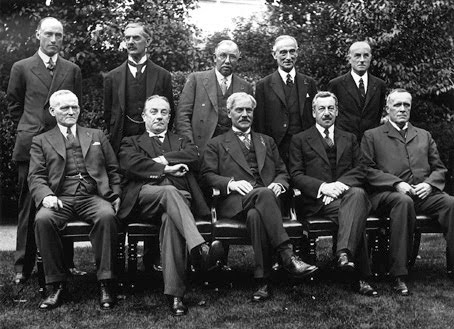

He played an important role in public life still, though. In 1920, Lloyd George made Samuel high commissioner for Palestine. Although he was not a believer, Samuel was an outwardly conforming Jew and, by 1914, had become a Zionist; as such, he had played a role in paving the way for the Balfour Declaration. As high commissioner, Sir Samuel (as he now was) faced the problem of keeping the balance between Jewish immigrants and their Arab neighbours. He did much to pacify the Arabs whilst allowing Jews to settle, but that was as much as he could do. For good or ill, he must be regarded as one of the founders of the modern Middle East, along with Gertrude Bell, Lawrence of Arabia and King Abdullah of Jordan (all pictured with him in 1921, below).

He played an important role in public life still, though. In 1920, Lloyd George made Samuel high commissioner for Palestine. Although he was not a believer, Samuel was an outwardly conforming Jew and, by 1914, had become a Zionist; as such, he had played a role in paving the way for the Balfour Declaration. As high commissioner, Sir Samuel (as he now was) faced the problem of keeping the balance between Jewish immigrants and their Arab neighbours. He did much to pacify the Arabs whilst allowing Jews to settle, but that was as much as he could do. For good or ill, he must be regarded as one of the founders of the modern Middle East, along with Gertrude Bell, Lawrence of Arabia and King Abdullah of Jordan (all pictured with him in 1921, below).

Interestingly, Samuel wanted to settle in Palestine, but his successor wanted him to leave. He would continue to take an interest in the idea of a Jewish homeland (though was often accused of backsliding on the issue by more trenchant Zionists). He opposed the Peel Commission’s recommendations for the partition of Palestine; he opposed similar proposals after the war. He supported the new state of Israel, however, and was an honoured guest when he visited in 1949. The moderation of his Zionism was evident though: he also crossed the ceasefire line to visit an old friend, now King Abdullah of Jordan.

Upon his return to Britain, Baldwin commissioned him to write the Samuel Report, into the state of the mining industry. The report itself, co-written with William Beveridge, was bestseller, but neither the miners nor the coal owners accepted his recommendations. The General Strike followed, in which Samuel played a conciliatory role, doing much to broker its end.

The following year saw Samuel return to domestic politics as Liberal Party Chairman. He loyally supported Lloyd George, despite his misgivings about the Goat’s character and the Lloyd George Fund. Some of his old political creativity returned too: he was one of the authors of the Yellow Book, as Britain’s Industrial Future (1928) was better known. Though Samuel returned to the Commons in 1929, the Liberal revival (which saw them win 24% of the popular vote) only yielded 59 seats. Furthermore, the party split once more, this time over Lloyd George’s refusal to vote Labour out of office. Samuel took Lloyd George’s line, and was actively involved in lengthy, though fruitless, discussions with Labour about the possible introduction of proportional representation.

The following year saw Samuel return to domestic politics as Liberal Party Chairman. He loyally supported Lloyd George, despite his misgivings about the Goat’s character and the Lloyd George Fund. Some of his old political creativity returned too: he was one of the authors of the Yellow Book, as Britain’s Industrial Future (1928) was better known. Though Samuel returned to the Commons in 1929, the Liberal revival (which saw them win 24% of the popular vote) only yielded 59 seats. Furthermore, the party split once more, this time over Lloyd George’s refusal to vote Labour out of office. Samuel took Lloyd George’s line, and was actively involved in lengthy, though fruitless, discussions with Labour about the possible introduction of proportional representation.

By the time the Labour government collapsed in the teeth of a sterling crisis in 1913, the Liberals had in effect split. When the National Government was formed, Lloyd George was ill. The Simonites were now giving birth to the Liberal Nationals, as Lloyd George’s deputy, Samuel was the de facto leader of the rest, who were now nicknamed the Samuleites. As such, Samuel returned to the Home Office.

Once more, his tenure was both short-lived and unhappy. The general election of 1931 saw the Liberal vote halved. The introduction of tariffs saw the Simonites become, in effect, Conservatives. At first, Samuel remained in office; then, in September, under fierce criticism from his own supporters, he resigned. At first, the Samuleites still sat on the government benches but, the following year, they crossed the floor.

Samuel’s decision to join the National Government earned him the undying hatred of Lloyd George, who quickly resorted to anti-Semitism. This was nothing new for Samuel. Back in 1912, Samuel had been implicated (wrongly) in the Marconi scandal, primarily because he was Jewish; the other Jewish member of the cabinet, Sir Rufus Isaacs (who, as Lord Reading, was the first foreign secretary in the 1931 National Government) was similarly embroiled. Back in 1914, Lloyd George had described Samuel as an ‘ambitious and grasping Jew who with all the worst characteristics of his race’. Later, Lloyd George would say of Samuel and Simon (who many, mistakenly, took to be Jewish) that at least he was ‘a bloody sight better than two Jews’. He also quipped that ‘when the circumcised Samuel they threw away the wrong bit’. After 1931, his attacks of Samuel were personal, vitriolic and bitter: he compared Samuel’s attempt to carve out a new Liberal position to the ‘vomit of a sick dog’.

Liberalism did not revive and, in 1935, Samuel lost his seat. He would never hold office again. He hoped that Churchill would call upon him in 1940, but his age and his previous support for appeasement scuppered that. He had by then taken a peerage, and settled into the role of elder statesman. He published several undistinguished works of philosophy and even a Utopian novel (right): none are read now. He became a popular radio and TV personality, thanks to the hugely popular programme The Brain’s Trust. He gave Britain’s first ever TV party political broadcast in 1951. You can see him on a campaign podium in the same election, here.

Liberalism did not revive and, in 1935, Samuel lost his seat. He would never hold office again. He hoped that Churchill would call upon him in 1940, but his age and his previous support for appeasement scuppered that. He had by then taken a peerage, and settled into the role of elder statesman. He published several undistinguished works of philosophy and even a Utopian novel (right): none are read now. He became a popular radio and TV personality, thanks to the hugely popular programme The Brain’s Trust. He gave Britain’s first ever TV party political broadcast in 1951. You can see him on a campaign podium in the same election, here.

Even his biographer admits that Samuel was not a likeable man, and that the frequent hostility he faced owed more to that than anti-Semitism. Nor was he in the front rank of political life. Nonetheless, he is, one of only three men since 1900 to have been home secretary twice; he is one of five home secretaries since 1900 to have gone on to be a party leader also (six if you count Asquith, seven if you include Clynes who was home secretary after being Labour leader). Her remains the only man to have been home secretary whilst also being leader of his party. Perhaps, above all else, Samuel helped keep the idea of Liberalism alive. Back in his youth, his closest friend and fellow affiliate to the Rainbow Circle had been Charles Trevelyan. In the 1920s, as many of their ilk did, Trevelyan crossed the floor to Labour. Others, like Churchill or Simon, jumped ship to the Conservatives. Samuel remained a Liberal and Liberalism almost died, but in the end clung on. Not long before his death in 1963 he saw the great Orpington by-election win that heralded a Liberal recovery of sorts. Thus, his great age allowed him to the last link between the Liberal Party of Asquith and the Liberal party of Jo Grimmond.

On a lighter note, Sir Herbert is surely the only British home secretary to have a beachfront boulevard named after him (in Tel Aviv) and a brand new hotel in Jerusalem.

1 thought on “The Home Secretaries (5): Herbert Samuel”