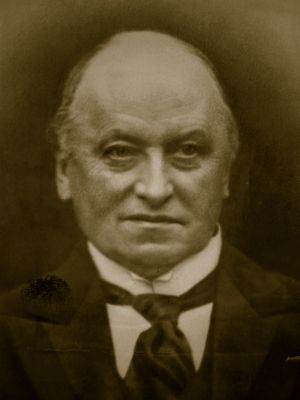

George Curzon, marquess of Kedleston

George Curzon, marquess of Kedleston

Conservative, in Lloyd George’s National Government, 1919; under Bonar Law, 1922-23 and Baldwin, 1923-24.

It is easy to depict George Nathaniel Curzon as the last of his kind. In fact, there would be later foreign secretaries from the House of Lords (the Marquis of Reading, in 1931, Alec-Douglas Home under Macmillan and Lord Carrington under Margaret Thatcher). But there is something to it. Curzon was the last to give the grand touch: if you wanted a genuine toff who looked the part, Curzon’s your man.

He was a bookish, rather brilliant child, who famously endured an upbringing under a tyrannical and sadistic nanny, a prep school master who was brilliant, and sadistic, and an Eton housemaster (not head of his own house) who recognised his intellectual gifts and fostered his love of art and history. From this, he acquired a passionate and boundless ambition.

At Balliol, Oxford, two friends wrote a snippet of verse about him, which would dog him for the rest of his life:

My name is George Nathaniel Curzon,

I am a most superior person.

My cheek is pink, my hair is sleek,

I dine at Blenheim once a week.

The air of haughtiness would do him some good, and no little damage, in his political career.

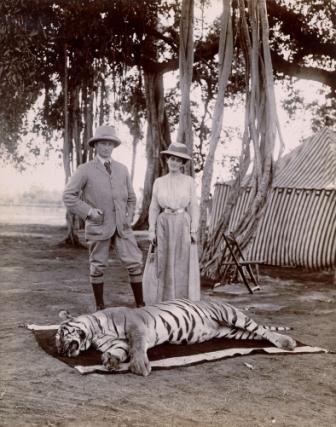

There was substance to him, though. At both Eton and Oxford, he won a raft of academic prizes; he was president of the Oxford Union. His first great setback was when he narrowly missed a first in Greats; he reputedly swore to spend the rest of his showing the world that examiners had it wrong. He wrote history then, essays on the likes Sir Thomas More of the emperor Justinian, prize-winning essays at that; he won a fellowship at All Souls. More importantly, he then embarked upon the three great passions of his life: women, politics and travel.

He returned from years of travel in Asia, and a brief spell as under-secretary of state for India, in time for Salisbury’s victory in 1895. He then became under-secretary of state at the Foreign Office. The prime minister, Lord Salisbury was also foreign secretary, thus Curzon was the government’s foreign policy spokesman in the Commons. Cabinet office surely awaited, but Curzon wanted to be viceroy of India.

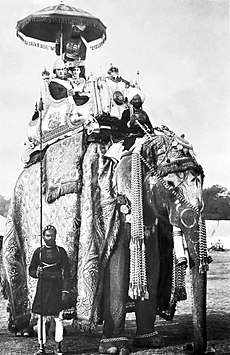

As viceroy, Curzon gained vast experience as a ruler and administrator, and was credited with a range of important and progressive reforms, though not with furthering the idea of Indian self government in the slightest. At the same time, he developed a lingering taste for imperial flummery and an even more grandiose manner that would do something to undermine him in the end. He also lost out in a bitter battle with Lord Kitchener for civilian control of the military: his defeat and resignation perhaps shows that for all his gifts Curzon lacked political nous and, as they say, elbows.

When he returned, it seemed that Curzon’s career was over. Balfour even refused to grant the earldom many, including Curzon, believed was his due; Campbell-Bannerman followed suit. He didn’t stand in the 1906 election, in part due to ill health, and in 1907 became an energetic chancellor of Oxford university (his ideas for reform were too radical at the time, but were adopted after the war). In 1906, his wife died in his arms. He would have other loves, and would marry again, but not happily; his coffin was made from wood hewn from the same tree as his much beloved Mary.

Although he finally entered the Lords in 1908, opposition politics bored him. He did himself no favours in the House of Lords crisis. At first, he had supported the ditchers, those who believed that the Lords should oppose Asquith ‘to the last ditch’. When, however, he realised Asquith would go through with his threat to create a Liberal majority in the Lords, he changed his mind. It was sensible, but earned him the virulent hatred of the Tory right (who were not people minded to forget, or forgive, easily).

It had seemed that Curzon was now set firmly in the role of elder statesman, substantial patron of the arts and scholarship, and restorer of his estates. Like Balfour, it was war that restored his fortunes. In Asquith’s coalition he was lord privy seal, but frustrated by a lack of ministry or some other outlet for his formidable administrative talents. That frustration surely played a part in his support for the move to create a war committee, that lead to the fall of Asquith. He was, like his other Tory colleagues, frustrated by Asquith’s leadership. Beaverbrook asserted that Curzon had assured Asquith of his support, only to jump ship late on; Beaverbrook, not for the first or last time, was being less than honest.

Under Lloyd George, Curzon returned to the front rank. As lord president of the council, and leader of the House of Lords, he was a member of the war cabinet. He was never one of Lloyd George’s confidants, however. He disagreed with the Balfour declaration (the clause that promised to respect the rights of Arabs was his); he opposed Montagu’s plan to advance Indian self-government. Nonetheless, he remained a staunch supporter of the government, and the war.

In 1919, Curzon was given charge of the ceremonial remembrance of that war. The cenotaph, the last post and the burial of the unknown soldier all came under his aegis. Such was the public response, Armistice Day and Remembrance Sunday became annual rituals, Curzon’s permanent legacy to our national life.

He was also given charge of the Foreign Office whilst Balfour, foreign secretary, was with Lloyd George at Versailles. It was a curious arrangement, and it was not fully resolved when Curzon took over from Balfour in October, 1919. As foreign secretary, He played second fiddle in all matters concerning Europe. Nonetheless, there was plenty to keep Curzon busy in the Middle East. Despite disagreements, especially over The Mandates (Curzon favoured Arab self-government under British tutelage), the arrangement worked well enough: Curzon got his way over a treaty with Persia, the government of Iraq and de jure independence for Egypt.

The relationship with Lloyd George would break over the issue of Turkey, just as Tory support for the coalition unravelled. In 1919, Curzon had maintained that whilst Turkey had lost its middle eastern territories, it should keep its territories in Anatolia. In particular, he opposed the handing over of Smyrna, Thrace and some islands to Greece; he also opposed the idea of stationing Allied troops in Asia Minor. Lloyd George was won over by the Greek nationalist leader, Venizelos: in the treaty of Sevres, the Greeks got what they wanted.

Curzon may have had a blind spot about Indian nationalism, but he was far more sensitive to the nationalism of the near and Middle East. He predicted that the settlement would prove unsustainable, and he was proved right. It helped provoke a Turkish nationalism that would see the rise of Mustapha Kemal and the .creation of modern Turkey: the Turkey that would ‘throw the Greeks into the sea’. Furthermore, the division of labour between Curzon and Lloyd George had its fault line in a Turkey that was both in Asia and Europe.

Curzon spent much of 1921 trying to persuade the Greeks that discretion was the better part of valour: that is, to try and hang on to Smyrna would be self-defeating. The Greeks were not minded to listen and then, for much of 1922, Curzon was ill. By the time he returned to work, the Turks were on the way to taking Smyrna.

That left a small allied force on the Asian shore of the Dardanelles, officially a neutral zone. Curzon, once more, advised discretion. Lloyd George went ahead and issued a press statement threatening the Turks. This was enough to persuade the French and Italians to withdraw, leaving a token British presence at Chanak. Curzon then went to Paris, and negotiated a deal with the French that promised, in effect, to give the Turks what they wanted after a decent interval. This, in turn, provoked a revolution in Greece. This led Lloyd George, backed by Churchill and Lord Birkenhead, to issue an ultimatum to the Turks: leave Chanak alone, or else.

It was a dangerous misjudgement: General Harington’s Force was tiny, Britain was isolated and there was no appetite for war at home, least of all among his Conservative cabinet colleagues. In the end, Harrington averted conflict by claiming he was unable to deliver the ultimatum, even that his code breaking apparatus had failed.

Once again, Curzon had been proved right. He went on to negotiate a solution along with the French which, in essence, gave the Turks what they wanted, but averted a humiliating British defeat. It also broke his relationship with Lloyd George. When Lloyd George made another public attack on the Turks, and Curzon learned that he had been talking to the Italians behind his back, he handed in his letter of resignation.

He needn’t have bothered. Lloyd George was all but finished. Already, the Chanak Crisis saw Bonar Law return to the fray, writing to The Times, to say that Britain should not aspire to be the ‘policeman of the world’. Curzon was one of those who now persuaded Bonar Law to turn against Lloyd George, and his own party leader Austen Chamberlain; when Bonar Law made his comeback at the Carlton Club, both were finished.

Curzon had been the only major figure to serve in Lloyd George’s cabinets from start to finish; he was the only senior coalitionist on the Tory side to turn against him and go on to serve in Bonar Law’s cabinet, the so-called 2nd XI. In the aftermath of a comfortable election win, the now Conservative foreign secretary negotiated the treaty of Lausanne, which finally resolved the Turkish issue.

As such, as the only one of the grandees still serving when Bonar Law’s throat cancer compelled his resignation in May 1923, Curzon must have believed himself to have been the obvious successor. 20 years earlier, he might well have made it to Number Ten. Now, it was political circumstance that conspired against him.

The recently deposed Austen Chamberlain had been undermined by his support for the coalition and his inability to win the support of backbenchers, many of whom were the cohort of 1918. The backbenchers had no role in choosing their leader, but their support mattered, as events at the Carlton Club the previous year had shown. Like Chamberlain, Curzon was a one time coalitionist, and a grandee without a following.

The leadership, given that Bonar Law was an incumbent prime minister, was in the constitutional gift of the king. In practice, the king took advice. Senior cabinet figures were sounded out, and great weight was given to the views of the outgoing prime minister. This time, Bonar Law gave no view. The man charged with taking soundings was the king’s secretary, Lord Stamfordham, who later confessed to being antipathetic to Curzon. Another Tory grandee, AJ Balfour, advised that it was no longer tenable for a prime minister to be in the Lords: the Commons were now where the real power resided, and the official opposition, Labour, had almost no representation in the upper house. Stamfordham gratefully took this advice, as well as misinterpreting Bonar Law’s silence as opposition to Curzon. The king, who no more wanted Curzon than Stamfordham, gratefully seized upon his secretary’s words.

Curzon was, famously, summoned to Downing Street, expecting to be told good news. When Stamfordham, instead of asking him if he would be a available to kiss hands (and thus become prime minister), asked him for his views on Baldwin, Curzon had to ask to be excused and retired to the lavatory to weep.

He considered retirement there and then, but stayed on. His primary task was to resist French attempts to use the Ruhr Crisis to break up Germany. He opposed Baldwin’s decision to go the country in 1923, an election that lost Curzon the Foreign Office, when Labour entered government in January 1924. When Baldwin won a landslide that same year, Curzon was not offered his old job, much to his bitter disappointment. He accepted the role of, once again, lord president of the council, which he held until his death in 1925.

Neither the political fates, nor many of his contemporaries were kind to Curzon. Even his high points were never unalloyed. And there were achievements. He was also often right, though he just as often failed to have his advice taken. As foreign secretary, he was in the shadow of Lloyd George, and then had his time cut short by the misjudgement of the man who had been given the prize he believed should have been his. As is often the way in politics, the most intelligent and perceptive voices can sometimes antagonise lesser minds; they can also appear arrogant, or even be so. Nonetheless, Curzon was one of four viceroys since 1900 to have also been foreign secretary. If Curzon was, in some ways, the last of the Victorian grandees to grace the foreign office, he also deserves to be remembered as one of a rare species: an inter-war foreign secretary who got more right than he got wrong.

Thank you for this, it was really interesting.

I came here because of the recent furore about taking down Curzon’s statue. I have a colourful impression of Curzon because 20 years ago I picked up a book written by a Daily Mail journalist named Mosley, a biography of Curzon apparently commissioned by one of Curzon’s political enemies. It was hilarious, but I could never be sure how much of it was true.

At any rate, it’s nice to see a much-maligned figure be given his just deserts. Curzon was a sufficiently significant personality to be remembered after his death, and for a statue to have been erected (unvailed by Baldwin!) in the first place.

LikeLike