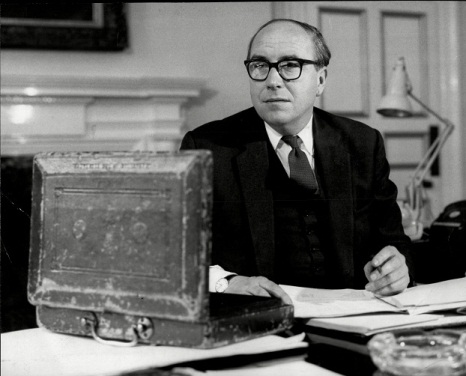

Roy Jenkins, 1967-70

Roy Jenkins, 1967-70

Labour, under Wilson

You can read about his time as home secretary and the rest of his career here.

After the devaluation crisis, Jenkins was simultaneously the leading figure in Wilson’s government, Wilson’s most likely successor and the man under the most pressure in an intensely febrile period in British political history.

At the root of the government’s problems was the economy. Devaluation was not a panacea. To work, it required deflation. Any chancellor has his work cut out when devaluation is required. By their very nature, the majority of the cabinet represent spending departments; each minister sees the defence of his own department as their duty. Deflation required retrenchment. Thus, given the need for spending cuts, a cabinet battle-royal was all but inevitable when it came to the 1968-69 spending round. Swingeing cuts in defence meant the immediate implementation of the East of Suez policy, which saw Britain withdraw from its commitments beyond NATO. They also saw Britain cancel its order for the F-111 fighter. Both proposals were bitterly opposed by Denis Healey, the defence secretary, with a torrent of foul language. They were also opposed by George Brown, because of the damage they did to relations with the Americans.

The process was made all the bloodier by the fact that this was a Labour government. One very typical George Brown moment came when the education secretary, Patrick Gordon-Walker, proposed to save money by putting off raising the school leaving age to 16, in favour of continuing to increase university student numbers. ‘May God forgive you,’ said Brown passionately.

Nor was Jenkins helped by the politics of it all. Jenkins was clearly a possible successor to Wilson, and was also a man of Labour’s right. He was thus a target of rivals, and of the left. He also faced jealousy. His erstwhile friend, Tony Crosland, clearly envied Jenkin’s rise; Callaghan was a wounded animal.

Knowing the depths of the problems he faced, even the seemingly insouciant Jenkins lost sleep. Pushing the cuts through required 32 hours of cabinet meetings and Jenkins spoke for eight of them, and had to remain on top of every aspect for the other 24. Jenkins won the day, but there was metaphorical blood on the table. Brown threatened to resign, as usual. Healey fought himself to a standstill. In Tony Benn’s view, Jenkins came out with great credit.

In Benn’s view, Wilson didn’t. In the end, Wilson backed his chancellor, though he probably had little choice in the matter. Taxes went up, and £716m worth of cuts were imposed. Jenkins himself described it as the ‘arctic winter’. Nor was it immediately effective. 1968 saw the government force a week’s closure on the London gold market in response to American demands and the pressure Vietnam was putting on the dollar. 1969 saws a further £340m in tax rises, and the bank rate reach 8%.

The danger was that devaluation would cause inflation. If devaluation and deflation was to work, there needed to be a measure of control over pay. In 1968, Wilson created a new ministry of employment and productivity. He gave its new minister, Barbara Castle, control of prices and incomes policy. He had first thought of giving Castle the Department for Economic Affairs. Instead, her appointment to employment represented a victory for Jenkins and the beginning of the end for the DEA: it was formally dissolved in 1969.

Wilson had famously claimed that devaluation would not affect ‘the pound in your pocket’. It did, as we know well from recent experience. Prices went up, and living standards were squeezed. A wave of strikes ensued. The government remembered the 1966 seaman’s strike with some bitterness. It seems that in appointing Castle, a minister known for being both tough and single-minded, Wilson had at last decided to bite the trade union bullet.

The problem was that, in doing so, Castle was also biting the hand that fed. One night, at Chequers, Wilson, Jenkins and Castle met with some of the most powerful trade union leaders: the union men all made their outright opposition to any attempt to regulate Labour relations known. Wilson, Castle and Jenkins went ahead with the publication of Castle’s In Place of Strife in 1969. If it was to become law, Castle needed to overcome opposition from the unions and some Labour backbenchers. To do that she needed the unequivocal support of the cabinet.

Perhaps a few years earlier, Wilson could have forced the issue. By 1969, however, Wilson was a diminished figure. Where once his popularity in the country gave him authority, now his poor poll ratings made him vulnerable. He was, like John Major after him, extraordinarily thin-skinned about criticism. He famously threatened to sue the BBC after a comedy show had asked how one tell if people were lying by their body language:

But what’s the tell-tale sign with Harold Wilson? What’s the piece of body language to look for if he’s lying?

There was a dramatic pause:

When you see his lips move.

Underlying this was a deepening paranoia about a plot against him, and his suspicions were turned firmly on Jenkins. In a cabinet meeting in June 1968, Wilson had turned on Jenkins and accused him of being behind press leaks attacking him. Jenkins demanded to speak with him alone. After Wilson spoke to him, and Crossman, he apologised. In the weeks before, some of Jenkins supporters on the backbenches had been angling for Wilson’s removal. Had Jenkins resigned that summer, Wilson may well have been forced out. Instead, he hesitated and all was lost. Jenkins would later claim that he did not give the signal to his supporters because he was preoccupied by Treasury business. No one else really believed that, then or now.

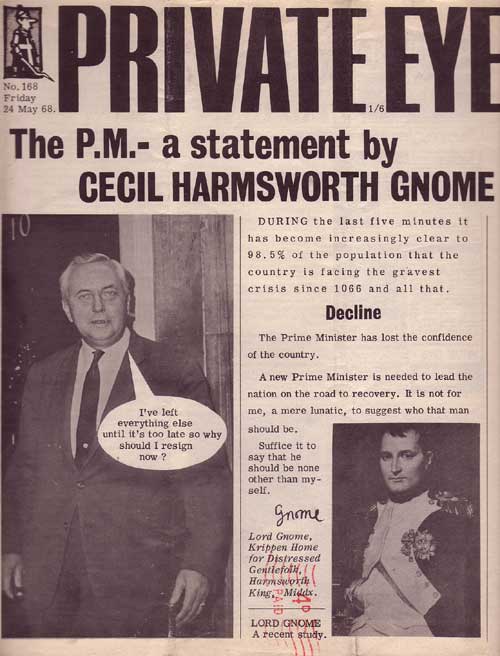

It seems that, come the moment, caution triumphed over ambition. There was another context. For some time, Cecil Harmsworth King, the press baron, had been making noises about the need for a national government. King was the proprietor of Britain’s biggest selling daily paper, the Daily Mirror. The question was, who would be 1968’s Lloyd George? King variously suggested Barbara Castle, Denis Healey and Roy Jenkins. Given Jenkins’ liberal sympathies and his later creation of the SDP, we might think such an idea might have appealed. In fact, he made it clear to King that he wasn’t interested. At this time, Jenkins was still cut in the Labour cloth he was born into.

King finally set on Lord Mountbatten as the figurehead, and it seems that Mountbatten did take the idea seriously, before finally coming to his senses. King went ahead anyway, publishing a front page leading article calling for Wilson to go and for a new government to be established. In the end, it was King that suffered: a shareholder revolt saw him lose his position as chairman of IPC. Any attempt to oust Wilson was now tainted by King’s madcap scheme.

Any chance In Place of Strife had was scuppered by James Callaghan’s outright and public opposition to it, and Wilson’s inability to deal with Callaghan. When Jenkins saw the writing on the wall, he abandoned Castle, something later regretted. In Place of Strife was now dead in the water: the question was, would Wilson go down with it? Once again, Jenkins refused to strike. Perhaps this time he feared that the victor would be a rejuvenated Callaghan. It could also be that he assumed the prize would be his anyway. Privately, Wilson had assured Jenkins that he would not serve another full term, and that he saw Jenkins as the only possible successor.

Political history is littered with the corpses of likely successors to prime ministers, many of them one-time inhabitants of number eleven (just ask George Osborne). Both Jenkins and Wilson expected Labour to win in 1970. Had they done so, Jenkins might well have succeeded Wilson. Labour didn’t win in 1970, and Jenkins had lost his chance: that chance, or chances, had come when Jenkins was chancellor. Perhaps, like Rab Butler before him, he lacked the elbows required. Jenkins recognised as much in his memoirs, noting that the likes of Lloyd George, Macmillan or Thatcher did not let such moments go.

Jenkins is often blamed for Labour’s defeat in 1970. His budget that year was certainly not a Butler-style pre-election give away. However, in the budget’s aftermath Labour were ahead in the polls, as they were until a week before polling day. If Jenkins was to bear some of the blame it might be thought that the necessary deflationary policies should have come earlier, in an emergency post-devaluation budget. Or, that the ditching of In Place of Strife did Labour some harm. Jenkins, as home secretary, had been the father of the Race Relations Act that led Enoch Powell to make his notorious Rivers of Blood speech: Powell certainly cost Labour votes in 1970. In the end, as a senior member of the government, Jenkins takes some of the blame. More might fall upon Wilson, or Alf Ramsey’s decision to substitute Bobby Charlton with 20 minutes to go of the World Cup quarter-final England lost on the Sunday before polling day.

Jenkins record at the Treasury was creditable, though. It is sometimes overdone. He had steadied the ship, for sure. By 1970, there was a trade surplus, sterling was stable and the economy was growing. However, the trade surplus was insecure, sterling was still vulnerable in a very unstable international situation, and inflation was building. If Jenkins inheritance was to be made more permanent, Jenkin’s successors would have to be giants. Instead, Edward Heath gave us Anthony Barber, and that’s another story, and very sorry one at that.

Jenkins remains one of ten chancellors since 1906 to have also served as home secretary. He was of 13 chancellors who were also a party leader (though in his case, of another party). Like Rab Butler, a figure he resembles in some ways, he remains one of the lost leaders. Or, as with Gaitskell too, one of the potentially great prime ministers we never had. He was, however, the outstanding figure in Harold Wilson’s 1964-70 governments, and much else besides.

1 thought on “The Chancellors (24): Roy Jenkins”