By 1923, the civil war was over. The anti-treaty forces had been crushed, and the new Free State was established. The civil war left its legacy, though, not least in subsequent politics: the two sides of the civil war gave birth to the two political parties that have dominated Irish politics ever since.

By 1923, the civil war was over. The anti-treaty forces had been crushed, and the new Free State was established. The civil war left its legacy, though, not least in subsequent politics: the two sides of the civil war gave birth to the two political parties that have dominated Irish politics ever since.

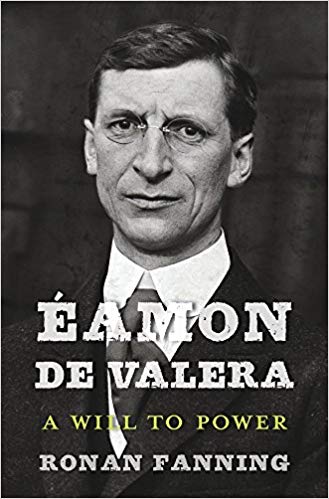

The pro-treaty side that now governed (above, in 1923) formed a party that, by 1932, had coalesced into Fine Gael. Meanwhile, Eamon de Valera created Fianna Fail (below). It went on to become its largest party in independent Ireland, as it would remain until 2011.

If de Valera’s conduct in 1921-22 was at best deeply mistaken, and at worst malign, head discovered statesmanship quickly thereafter. Having lost his seat, he contemplated leaving politics. Instead, in 1926, he broke from and effectively broke Sinn Féin. Then, in 1927, he ate his old words about the oath: Fianna Fáil held their noses, took the oath, entered the Dáil and got on with constitutional politics.

De Valera won power in 1932, on the back of the slump. In 1931, the Statute of Westminster had removed the last vestiges of London’s control over dominion parliaments. Taking advantage of the freedom to achieve freedom that Collins et al had given him, de Valera gradually stripped away the last vestiges of British authority: he abolished the oath, removed the powers of the governor-general and moved him into a small house in the suburbs, as well creating a separate Irish citizenship.

Britain did not react well. It imposed trade sanctions; in response, de Valera (seen at the top in London in 1932) refused to make the loan repayments due for land purchase made under the pre-war Land Acts. A trade war ensued (de Valera was a believer in autarky, at least in theory). The Irish economy languished, and many of its people were left in a not always genteel poverty. None of this stopped de Valera moving further to cut the ties with Britain. In 1936, he abolished the office of governor-general. Then, in 1937, he introduced a new constitution: Eire, as the state was now known, was independent.

Characteristically, de Valera’s constitution was a study in ambiguity. It made no mention of the word republic, though the word sovereignty was used liberally. It gave the state a president, though one with little actual power. It claimed sovereignty over the north, but without any real intention of acting upon it. It did not make the Catholic Church the established church, but it did acknowledge its special place in the nation’s life.

When Chamberlain came to power in 1937, he moved to repair Anglo-Irish relations. The debt issue was resolved and the constitution recognised; Britain also gave up the treaty ports. When war came, Eire remained neutral. Neutrality spoke powerfully of Irish independence, and de Valera knew that anything other than neutrality would quickly have opened old wounds. London even toyed with the idea of coming out for Irish unity in return for Irish support in the war. That de Valera would never have countenanced the idea tells us much about the place of the north in Dublin’s priorities. Nonetheless, Britain had good reason to resent Ireland’s neutrality. In particular, the fact that they were not allowed to use the treaty ports made the Atlantic convoys riskier (whose supplies were destined for Ireland as well as Britain).

Ireland’s neutrality had its limits, though. Somewhere around 70,000 men and women who had been born in the Free State served in British armed forces; another 100,000 were working there. For some, this was a political act: in opposition to Nazism and Fascism, in support of democracy, support for Britain. For many, it was simple economic necessity.

A feature of modern Irish life has been the misery memoir, such as Frank McCourt’s international bestseller Angela’s Ashes. Written in the ‘nineties, as the Celtic Tiger roared and Ireland underwent rapid socio-economic change, many looked back to the old Ireland as a place of grinding poverty and puritanical theocracy. It is, of course, easy to overdo both. Those of us who knew the old Ireland sometimes are also prone to look back on it with a warm nostalgia, at least in part.

A feature of modern Irish life has been the misery memoir, such as Frank McCourt’s international bestseller Angela’s Ashes. Written in the ‘nineties, as the Celtic Tiger roared and Ireland underwent rapid socio-economic change, many looked back to the old Ireland as a place of grinding poverty and puritanical theocracy. It is, of course, easy to overdo both. Those of us who knew the old Ireland sometimes are also prone to look back on it with a warm nostalgia, at least in part.

But there was grinding poverty. The Emergency, was the wartime period was officially known, merely exacerbated existing trends in the Irish economy: it also showed that autarky was a busted flush. In short, Ireland’s industrial base was paltry and underdeveloped, and its agriculture backward. Its currency was tied to sterling, and it was wholly dependent upon Britain for coal and oil. Joe Lee made much of the comparison with a similar-sized small European nation: Denmark. The Free State does not come out well. However, looked at in a European context in an era when most European economies were not doing well, and were protectionist, Ireland’s growth rates were about average: it was the 1950s that saw it fall well behind.

De Valera is sometimes accused of wishing backwardness upon his people. He famously lauded a vision of a nation of comely maids and pure, sturdy farmers; he sometimes seemed to personify a kind of puritan Catholicism, and aversion to the modern world. There is some truth in that, though that was an outlook many others shared. It can also be overdone, however. Fianna Fáil’s most creative thinker, Seán Lemass (above), took the opportunity of wartime emergency powers to reform the state’s approach to the economy: Lemass looked to planning, state intervention and Keynesianism.

For all that, many ordinary people were very poor, as the above (from the Irish Press 1932 campaign against slum housing) shows. Living standards were lower than those in a depression hit Britain and Northern Ireland. Many working class children lived in slums, were malnourished and lacked basic healthcare. In 1943, an estimated 17.3% of Irish children had rickets. Around 120,000 people lived in slum tenements: about half of them were unfit for human habitation and beyond repair. Ireland’s infant mortality rate, 7% of all births (9% in Dublin), was shockingly high; at the same time, in the Great Depression, Britain’s was 1.5%. A government survey in 1941 revealed that 60% of mothers in Dublin were too malnourished to breast-feed their babies. For those a little higher up the ladder, things were hardly abundant. Gradually, forms of welfare (such as pensions) and medical provision were extended, and houses were built. However, provision was patchy and often at behest of religious charitable organisations.

And the problem was that many of Ireland’s charitable organisations were not very charitable, to say the least. The past twenty years has seen a grim and, at the time, barely spoken truth finally emerge. The truth is a story of systematic and horrendous sexual, physical and emotional abuse meted out by churchmen, nuns and those allied to them against defenceless children in institutions all across Ireland for decades. This was hardly unique to Ireland, or to the clergy (as anyone who has read John McGahern’s The Dark, with its broken, violent father, will know): though its extent remains shocking. Just as bitter a truth was the extent of the moral complicity of the church, the state and, it must be admitted, many Irish people: it was a part of national life and the life of national institutions. There were, of course, many wholly decent and well-intentioned men and women caring for others: there were even a few who spoke out. However, the abusers were left to get on with it or, at best, moved on to pastures new, but similar: blind eyes were turned towards institutions and abusive families. Problem children, poor children, ‘immoral’ or pregnant girls were safely hidden from view, from care, and far too often horribly mistreated.

And the problem was that many of Ireland’s charitable organisations were not very charitable, to say the least. The past twenty years has seen a grim and, at the time, barely spoken truth finally emerge. The truth is a story of systematic and horrendous sexual, physical and emotional abuse meted out by churchmen, nuns and those allied to them against defenceless children in institutions all across Ireland for decades. This was hardly unique to Ireland, or to the clergy (as anyone who has read John McGahern’s The Dark, with its broken, violent father, will know): though its extent remains shocking. Just as bitter a truth was the extent of the moral complicity of the church, the state and, it must be admitted, many Irish people: it was a part of national life and the life of national institutions. There were, of course, many wholly decent and well-intentioned men and women caring for others: there were even a few who spoke out. However, the abusers were left to get on with it or, at best, moved on to pastures new, but similar: blind eyes were turned towards institutions and abusive families. Problem children, poor children, ‘immoral’ or pregnant girls were safely hidden from view, from care, and far too often horribly mistreated.

What gave all this an especially hypocritical air was the Church’s teaching. Irish Catholicism in these years was fiercely puritanical, with an obsession about sex, sin and its punishment. Children were a gift from God. The importation and sale of contraceptives was made illegal in 1935. The church in these years is most associated with John McQuaid (left), archbishop of Dublin from 1940 to 1972. It is possible to overstate the influence the church, and McQuaid himself, wielded. It was, however, considerable. If independent Ireland was not actually a theocracy, there were times when it did a pretty good impersonation of one. The pervasive influence the church in Irish life gave it a great deal of power over its people; a people it sought to protect from the progressive, the Protestant and the impure. Above all, what the church did was lend force to Ireland’s, and de Valera’s, social conservatism: McQuaid would boast of Ireland’s success in resisting ‘modern aberrations’.

What gave all this an especially hypocritical air was the Church’s teaching. Irish Catholicism in these years was fiercely puritanical, with an obsession about sex, sin and its punishment. Children were a gift from God. The importation and sale of contraceptives was made illegal in 1935. The church in these years is most associated with John McQuaid (left), archbishop of Dublin from 1940 to 1972. It is possible to overstate the influence the church, and McQuaid himself, wielded. It was, however, considerable. If independent Ireland was not actually a theocracy, there were times when it did a pretty good impersonation of one. The pervasive influence the church in Irish life gave it a great deal of power over its people; a people it sought to protect from the progressive, the Protestant and the impure. Above all, what the church did was lend force to Ireland’s, and de Valera’s, social conservatism: McQuaid would boast of Ireland’s success in resisting ‘modern aberrations’.

In part, his railings against modernity reflected an underlying truth: Ireland did modernise. Despite the church, censorship, economic backwardness and social conservatism, the modern world could not be kept out altogether. There was an obsession with the moral threat of dance halls, for example, because there were a lot of dance halls, licensed and unlicensed, and a lot of dancing going on. There is also something to be said for the notion that the obsession with sexual sin made up for the lax approach Irish society had to financial probity: the gombeen man, the shady wheeler-dealer, was a staple of Irish life.

In McGahern’s Amongst Women (his masterpiece) the old IRA man, Moran, rails against the Ireland he lives in: an Ireland ‘run by gangsters’. The Republican ideal has faded and gone, and ‘half his family’ have left for England. Moran dominates the family that remains, in part by emotional and actual violence. It was also an Ireland in which The Dark was banned; McGahern also lost his teaching job (in part thanks to McQuaid). An Ireland that so often seemed dominated by mammy was, in reality, a Catholic patriarchy.

In McGahern’s Amongst Women (his masterpiece) the old IRA man, Moran, rails against the Ireland he lives in: an Ireland ‘run by gangsters’. The Republican ideal has faded and gone, and ‘half his family’ have left for England. Moran dominates the family that remains, in part by emotional and actual violence. It was also an Ireland in which The Dark was banned; McGahern also lost his teaching job (in part thanks to McQuaid). An Ireland that so often seemed dominated by mammy was, in reality, a Catholic patriarchy.

Like Moran’s children (and McGahern), young Irish people emigrated: in the ‘fifties, 1.4% of Ireland’s population emigrated each year, some 412,000 in total. Some went far, most went to Britain. Like all migrants, they left for a panoply of reasons, and many longed for home (though they more often sung about home than actually returned). Undoubtedly, though, emigration on that scale says much about the Irish economy, and society, in the years after independence.

By 1949, Ireland was a republic. That Republic of Ireland had underlying social and economic problems, and that the process of independence had exacerbated those problems. There is much that could have been done differently, and some elements of social and economic policy look like actual self-harm informed by wishful thinking.

And yet, those migrants did dream of home.

De Valera was no liberal. Social policy remained conservative and Catholic. There was censorship, and de Valera was not above using special powers against opponents. However, that was not de Valera’s only bequest. He had seen off political violence in the form of the IRA and Ireland’s would-be Fascist movement, the Blueshirts. His 1937 constitution entrenched liberal democracy in a Europe in which it was an endangered species. The Republic of Ireland was created by de Valera’s opponents: after 16 years in power, in a time of serious economic difficulty, Fianna Fáil had lost the 1948 general election. Fianna Fáil would return, but de Valera’s defeat betokens his greatest achievement. The Free State had become a stable democracy. The freedom to achieve freedom had been used, and in the end used wisely. In the end, Dev deserves his place in the pantheon.