If Irish nationalism had hid its head in the political and over the fundamental strategic realities of Anglo-Irish relations and northern unionism, the process of achieving independence exposed the other fairy tales, or unicorns as we seem to be saying nowadays, that underpinned nationalist political thought. If breaking up proved hard to do, the party that did the breaking, Sinn Féin, was broken in its turn, and Irish public life was poisoned for generations.

Constitutional Nationalist Unicorns: Political Realities, and the Limitations of Nationalism

As noted in part one, London was the great power: smaller Ireland the supplicant. This was made worse by the fact that Irish nationalists had never really needed to bow to realities before. In large part, this was because Irish politicians, at the turn of the century, did not govern in any meaningful sense. The Local Government Act of 1898 had created local councils, but national government was in the hands of Dublin Castle, which was answerable to the Chief Secretary, a member of the cabinet (from 1907-16, Augustine Birrell, left; you can read about him here). To put it simply, Ireland was not governed in the same way as the rest of the United Kingdom. To be fair, there were similarities to the constitutional arrangements with Scotland. However, Scottish politics was not separate: like then rest of the United Kingdom, it was about the clash of the great British parties and the United Kingdom general elections that decided its government.

As noted in part one, London was the great power: smaller Ireland the supplicant. This was made worse by the fact that Irish nationalists had never really needed to bow to realities before. In large part, this was because Irish politicians, at the turn of the century, did not govern in any meaningful sense. The Local Government Act of 1898 had created local councils, but national government was in the hands of Dublin Castle, which was answerable to the Chief Secretary, a member of the cabinet (from 1907-16, Augustine Birrell, left; you can read about him here). To put it simply, Ireland was not governed in the same way as the rest of the United Kingdom. To be fair, there were similarities to the constitutional arrangements with Scotland. However, Scottish politics was not separate: like then rest of the United Kingdom, it was about the clash of the great British parties and the United Kingdom general elections that decided its government.

That was not the case in Ireland. True, Irish unionists were Conservatives, but their Toryism had always been conditional; what mattered above all else was the maintenance of the union. Meanwhile, though, with the creation of the Parliamentary Party, Irish nationalists voted for a specifically Irish party, one than took no part in Westminster government. Thus, where there had been reforms, they had been the creation of enlightened British Westminster politicians on both sides.

This made the Parliamentary Party by nature a vehicle for opposition. Thus, home rule remained largely undefined. Ironically, in the end, it was the Westminster government that had to define what home rule meant in practice. When that definition went against nationalist aspiration, the party opposed it, as over the proposals to exempt northeast Ulster. Nationalism, and wishful thinking, triumphed over the facts of political life. The problem was that facts stubbornly refused to change, and Westminster governments had priorities and pressures of their own. Thus, any solution was always likely to fall short of nationalist aspirations, and the nationalists were unable to advance any alternative that might get the unionists on board. There was one realistic outcome: some form of home rule (something short of dominion status or, by 1921, dominion status) with partition. Twice, the nationalists rejected it. Home rule had never been clearly defined, and when the British defined it, the nationalists didn’t really like the outcome.

The Hillside Men: a republic means a republic, but what does a republic mean?

If wishful thinking was part of constitutional nationalism, the radicals were even more devoted to it. The pure ideal remained complete separation. In the United Kingdom of 1912, that wasn’t on the table. Thus, the radicals supported home rule. However, in Easter 1916, the radicals had their heads: they proclaimed their Republic. Not that it mattered much, because they had no chance of actually getting an actual republic (some even argued that they should become an Irish monarchy, under a German prince). However, the Easter Rising became the foundational myth of the new Ireland, and the republican idea came was part of the package. The sixteen dead men, the executed leaders (above), became Republican saints: to disavow the Republican ideal was to disavow them. The Sinn Féin party that won the 1918 general election was avowedly republican.

Well, after a fashion. Arthur Griffith (right) had founded the party in 1905, arguing that Ireland should follow the Hungarian model of a ‘dual monarchy’. Thus, Ireland would have its own parliament under the crown (which was essentially the same as Daniel O’Connell’s Repeal movement in the 1840s). In 1917, the party nearly split between monarchists and republicans: de Valera and Griffith brokered a compromise in which upon independence the Irish people could then choose their own government. Sinn Féin’s republicanism was, in fact, left carefully undefined.

Well, after a fashion. Arthur Griffith (right) had founded the party in 1905, arguing that Ireland should follow the Hungarian model of a ‘dual monarchy’. Thus, Ireland would have its own parliament under the crown (which was essentially the same as Daniel O’Connell’s Repeal movement in the 1840s). In 1917, the party nearly split between monarchists and republicans: de Valera and Griffith brokered a compromise in which upon independence the Irish people could then choose their own government. Sinn Féin’s republicanism was, in fact, left carefully undefined.

Ireland’s Dolchstoßlegende: Drunk on English Hospitality, or the Sober Realities of Negotiation

After defeat in the Great War, German right-wingers became attached to Dolchstoßlegende, or the stab in the back. This myth asserted that an undefeated Germany, and German army, had been stabbed in the back by the democratic civilian (and Jewish) politicians that signed the armistice. Those same politicians, the ‘November criminals‘ would compound the crime by signing the Treaty of Versailles. Germany had thus been betrayed by the traitors within.

In Ireland, the bloody conflict that began in 1919 ended with a truce in 1921. It was time to negotiate. That meant compromise. For those who had fed their hearts on the republican fantasy, that compromise would inevitably mean what they would see as betrayal: Ireland’s Dolchstoßlegende.

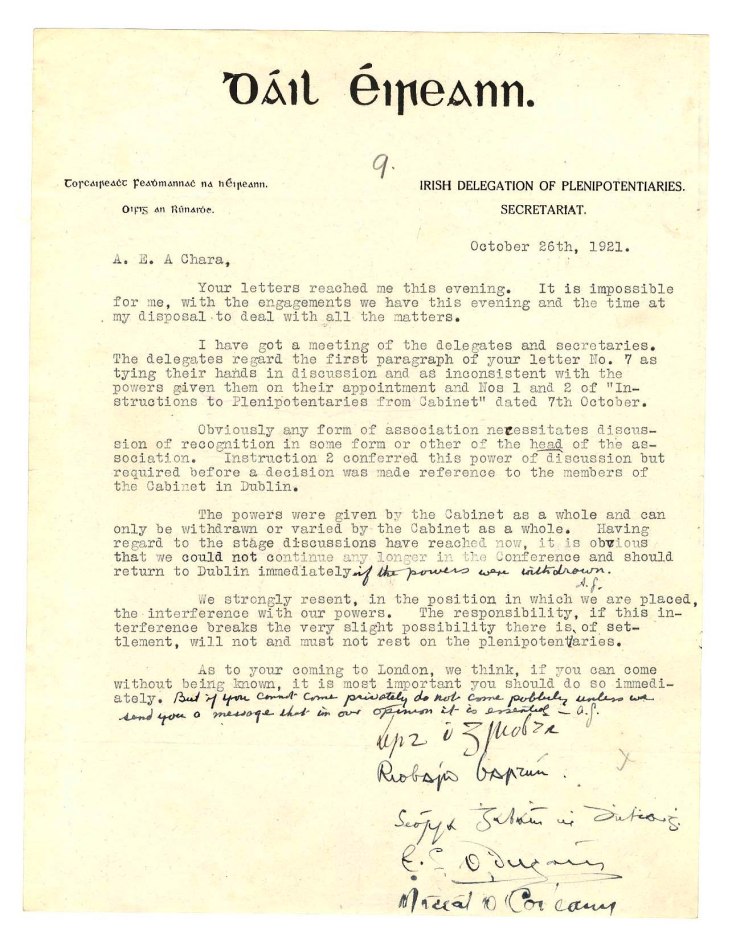

In those negotiations, there were some strengths to the Irish position. Sinn Féin’s spectacular win in the 1918 election, and the policy of abstention from Westminster, had done a great deal to raise a question over the legitimacy of the government of Ireland as it stood. Now, a parliament sat in Dublin, even if illegally: the first Dáil sat in 1919 (above). In a democratic age, the Irish voice had spoken. It might also be argued that the violence of 1919-21 did much to persuade the Westminster government that most of Ireland was no longer governable, unless its national aspirations were recognised. Not only that, but in a Britain recovering from four years of terrible warfare, there was no real appetite for more. In other words, London was willing to compromise.

There were limits to that willingness though. In the first place, Lloyd George was prime minister of a coalition dominated by his Conservative partners, the same men that had once so bitterly opposed home rule. They would, in the end, be dragged a good way further down the road than home rule, but there were limits.

Nor was it a negotiation of equals. We may now feel that Britain’s great power status had been as much undermined as it has been confirmed by the Great War, but it didn’t really look much like it the time. Famously, when it came to the last phases of negotiation, Lloyd George had made sure that the Irish plenipotentiaries met him in the cabinet room, with a map of British forces and their deployment around the world, and a barely veiled threat that, in the absence of agreement, those forces would be brought to bear upon Ireland. Did the Irish want peace, or war?

That bore upon another weakness in the Irish position. Come the truce, many IRA men had blown their cover and were now identified. Furthermore, Michael Collins (above) believed that, militarily, the IRA had achieved about as much as they could. Not only that, but Collins also knew that if it came to anything like open conflict between the IRA and the British army, the IRA would be destroyed (as their republican rump were by Free State forces in the civil war). In short, this time was the ripe time, their best chance of a deal.

Negotiation didn’t just imply compromise; it also implied definition. There was no definite proposal emanating from Dublin other than the undefined republic; in part, because the Irish headers knew that defining it would divide them. When the first communications were opened, de Valera remained studiously vague, doing little more than simply restating the public position. Ireland wanted a republic, whatever it was they meant by that. With only Irish red lines (Brits out) and republicanism (unicorns in) coming from Dublin, it was over to Lloyd George to try to frame a constitutional settlement. His solution was generous, but with limits: dominion status, with riders attached.

De Valera (above) was aware of this from the start. On his visit to London he rejected the idea and subjected his hosts to a lengthy account of the iniquities of Oliver Cromwell. Famously, Lloyd George described the experience of negotiating with de Valera as like ‘trying to pick up mercury with a fork’. When the time came to negotiate for real, de Valera chose to stay at home. His reasons for doing this have remained obscure, and controversial. It was not that de Valera was a completely doctrinaire and inflexible republican. In power, he would be supple and gradualist; in opposing the treaty in 1922, he was not an absolutist or separatist. It could be that his experience in London persuaded him that negotiations would go better without him. It might also be that by putting Collins at the de facto head of the Irish side in London, he hoped to tie the IRA and the hardliners to any deal that emerged. It might be that he hoped that by staying away, he could be the man to hold a divided Sinn Féin together. It is also is possible to take a more cynical view: staying away would give him the opportunity to indulge in some plausible deniability, when the inevitable compromise came home. It remained a fact that in 1918 Ireland had not voted for a republic as such. True, there had been elections in 1921 (though they were of a contested status), but even then republicanism remained less than precisely defined. That lack of definition suited de Valera politically: being in London would force him to define his position.

The Irish delegation, like Sinn Féin itself, was divided. Negotiations were complex and fraught. For both sides there would emerge what we now like to call red lines, and both sides had domestic political backs to watch. In the end, Collins led the Irish delegation in a recognition of what was political reality (they are pictured above, signing the treaty).

The British navy would have access to four ‘treaty ports’. The six counties of northeast Ulster would be treated separately, having what was in effect (ironically) a form of home rule: a devolved government under Westminster, but still returning MPs to parliament. The permanent nature of that partition was fudged by the prospect of a boundary commission. Most importantly, Ireland would have broadly the same constitutional status of the four white dominions in the empire (Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa). That would be tantamount to political independence. It thus included fiscal independence, something Griffith and Collins regarded as a major achievement. However, the Irish also undertook to meet their financial obligations to send money to London to compensate former landowners whose land had been forcibly sold off under the terms of Land Acts.

The real sticking point was symbolic. Britain insisted that the new state must keep its ties to the crown and the empire. Ireland would have a governor-general. The issue that would convulse Sinn Féin was related: the British insistence that all members of the new Irish parliament would take an oath of loyalty to the new Irish Free State, and to be ‘faithful to his Majesty in virtue of the common citizenship of great Britain and Ireland’.

That oath would bring about the effective end of Sinn Féin and lead the Irish Free State into civil war.

Give Them a Republic? Sinn Féin Torn Apart

The fact that the issue of the oath led to civil war in Ireland is rightly seen as symptomatic of Irish political nationalism’s obsession with symbolism. There is some justice in that, though it is probably true of all forms of political nationalism. It is also true that the same might be said of empires, and imperialists. The British had been insistent: there must be the oath. When Collins drew up the first Free State constitution, trying to bind a fractured Sinn Féin together, he omitted the oath. The British insisted that it was included.

That insistence came partly from imperialist instinct. Apart from Lloyd George himself, the other delegates on the British side were three of the big names in the imperialist firmament: for the Liberals Churchill, for the Conservatives Lord Birkenhead and Austen Chamberlain. It was also seen as a constitutional guarantor, especially by Birkenhead. For Lloyd George, it was a political necessity, which would help win over reluctant Conservatives.

In Ireland, the divisions it opened up were visceral. In the end, all the Irish delegates signed, persuaded by Collins and Griffith. For them, it was the best deal they could have got. On the night they signed, Lloyd George had given them an ultimatum: they could have peace or war, but they would have either now. Griffith laid strong emphasis on the fiscal autonomy they had won, notably the right to set their own tariffs. For Collins (with de Valera and Harry Boland, below), the choice was the one Lloyd George had given him: a war that the IRA could not win, or peace and statehood.

The seven-man Sinn Féin cabinet was split: four for, three against. The treaty was ratified by the Dáil, but only by 64 votes to 57. The debates, held in secret, were bitter and impassioned. The root of the opposition to the treaty was opposition to the oath, which was itself symbolic of an emotional attachment to the ideal of the republic. The delegates had been sent to negotiate a republic, not sign away the nation’s birthright, the argument ran. They had been lured by perfidious Albion, by English wiles: Collins had got ‘drunk on English hospitality and sold the republic down the river’. Had they only held their ground, negotiated differently, or brought the treaty home unsigned, things could have been different and the republic saved. They were now traitors, dishonouring the names of dead patriots. Unsullied and pure, the republic of the imagination (though arguably still undefined) must live on.

De Valera opposed the treaty, though his position was more nuanced than that of most. His proposed alternative, known as Document #2, was created during tghe negotiations, and had been sidelined by Collins et all (see above). It jettisoned the oath and dominion status, suggesting something like the status India would hold in the Commonwealth in 1947. It was couched in careful terms: it didn’t mention the word republic, for example. It was a creative and intelligent constitutional proposal, but in the context of the negotiations it was wholly unrealistic. Just as Collins attempt to hold the movement together by eliding the oath was doomed to fail, because it was unacceptable to Britain, so was Document #2. The unicorns had run out of road.

‘We Fed the Heart on Fantasies’: Civil War

The verdict of the Dáil was backed up in a general election. For the majority, as Collins had argued, peace and statehood were enough. In the end, he famously argued, it gave Ireland ‘the freedom to achieve freedom’. For the irreconcilables, that didn’t matter: Ireland was still tied to Britain, and the Republic had been betrayed.

Tragically, the result was civil war, hence John Joyce’s mordant quip above. The pro-treaty side won, but not before civil war had done what civil wars do. The anti-treaty side (led by de Valera, above), described by Eileen O’Faoláin (wife of the poet Seán) as ‘abstract fanatics’, fought with the doomed brutality of their type. Free State forces, with the panoply of state power behind, then reacted in kind: and unlike their British predecessors, they knew who their enemies were. When five Free State soldiers were killed by a mine in Co Kerry, Free State forces retaliated by tying eight Republicans to a mine and blowing them up. Among the 1,200 or so dead were Collins, who had signed the treaty, assassinated in his native Co Cork. Erskine Childers, one of the secretaries to the delegation, was on the other side and was executed by the Free State (you can read about him here). Griffith became president of the Free State, de Valera his bitter opponent. Shortly before Collins’ assassination, Griffith had died of a heart attack, worn down by it all: Collins is pictured at his funeral, below.

To quote Yeats’ Meditations in Time of Civil War:

We had fed the heart on fantasies,

The heart’s grown brutal from the fare,

More substance in our enmities

Than in our love…

In Diarmaid Ferriter’s words, the civil war ‘sank the middle ground’.

‘Much hatred, little room’: the Price of Freedom

That middle ground had, and could have, existed. The divide between Griffith and de Valera was actually pretty Jesuitical, until the oath enraged Republican emotion past the point of reason. Even before that, home rule could easily have been a step on the road to dominion status. Dominion status did, de facto, make Ireland independent. Ironically, it was de Valera who would go on to show that very fact when he took power in 1932. Collins and Griffith had been right: the Irish Free State gave Ireland the ‘freedom to achieve freedom’. In short, Ireland could have got where it ended up, becoming a democratic republic, from that very starting point.

Independence came at a cost. Ireland was partitioned and, in the end, partition would see the Troubles bequeathed us by the Provisional IRA. The home rule crisis, the Easter Rising, the war of independence and the civil war brought the gun into Irish politics: it has proved a fatal attraction ever since. The bitterness of civil war would frame the politics of the Free State and its successor state, the Republic of Ireland, thereafter. The new Ireland would, for far too long, be economically backward, overly theocratic and a net exporter of its people. For far too long, independent Ireland lived up to John Joyce’s quip.

Could there have been a different Ireland? Probably, yes. However, the way in which independence came, left us with an Ireland embittered in its discourse, an island divided by violent rhetoric and deluded to its political imagination. An Ireland made brutal by fantasy. To quote the poet again:

Out of Ireland have we come.

Great hatred, little room,

Maimed us at the start.

I carry from my mother’s womb

A fanatic heart.

For far too long answer to Ireland’s English Question was thus: the great hatred had won.